For Teacher Appreciation Week, What Makes a Great Teacher?

Knowing a lot has something to do with it...

Welcome! I'm Lauren Brown and this is my newsletter on education issues that impact all of us— parents, educators & concerned citizens. Today’s post is in honor of Teacher Appreciation Week and was inspired by my high school chemistry teacher, my dear friend and mentor/former history department chair/model of a great U.S. history teacher and Robert Pondiscio’s recent post that questions the widely-held belief that students need to like their teachers in order to learn from them.

It’s hard—no, impossible— to be a great teacher if you do not know your subject well. A great teacher must also genuinely like children or teenagers or whatever age group she works with. It is no good to just “love history” (or math, or English, or science or whatever subject you teach). Students know when their teachers don’t really like them. And that doesn’t end well.

But whenever one of my student teachers insisted that the reason they wanted to become a teacher is because they loved kids (they used to coach soccer or babysat or were a camp counselor or whatever) I would sigh. There are many professions in which one can work with kids, but if the profession you pick is “history teacher,” you ought to love history too. Sometimes my pre-service teachers would say they were influenced by a great history teacher they had and now they wanted to be that “great history teacher” for somebody else.

So what makes a great history teacher?

Let me start by describing a great science teacher, one of the best teachers I ever had: my high school chemistry teacher. Ms. Mueller had a reputation for being hard, tough, and even a little scary. Okay, a lot scary— she scared the crap out of me. And probably that’s not the greatest thing for students who might not be so good at chemistry and need help and are too scared to ask for help.

But Ms. Mueller was passionate about chemistry and she knew her stuff. She made sure you learned it too.

She had a lesson that was so good, it was actually famous throughout the school. It even had—get this— a title! (Do you remember the title of ANY lesson you had in high school? college?!) It was called "The Truth and Beauty Lecture." When you told other kids that you had Ms. Mueller for chemistry, kids who had already taken her class would ask, "Have you had the truth and beauty lecture yet?" and then exchange knowing looks among themselves.

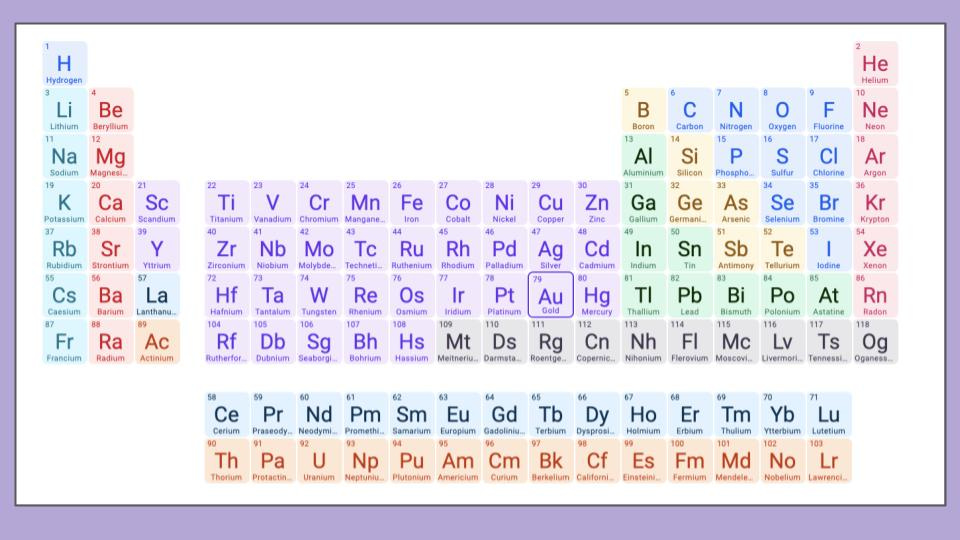

Years later, I still can remember the experience of that lesson. It started off like a regular day in her class. I was taking notes as fast as I could to keep up, and as I wrote, I thought to myself, hmm, this is pretty interesting. And then, whoa…actually, this is rather incredible. This is….amazing! And then, as she started to conclude, I realized, this is it! This is the Truth and Beauty Lecture! And Ms. Mueller would finish by explaining that everything she had just gone over demonstrated the truth and beauty of the periodic table. And while I have forgotten most of the details, I know that for at least one moment in my life, I understood the Truth and Beauty of Chemistry. Of Science. Of the Universe. And that is a pretty impressive feat to accomplish as a teacher.1

Ms. Mueller may not my favorite teacher, but she was one of the best. And, scary though she was, there was always a twinkle in her eyes and you could tell she liked kids. Especially on Fridays when she would sometimes start class by reading a poem because, she told us, the world needs poetry, and she wasn’t sure the English teachers were reading us enough of it. Truth and beauty.

Likely, Ms. Mueller was not the favorite of most students, even though she was widely recognized as the one who would actually teach you chemistry (and if you were really brave, get you college credit by getting a 4 or 5 on the AP Chem test). Teachers with reputations for being hard, tough, and scary typically are not adored. Kids like teachers who are funny or nice.

I remember, years ago, overhearing a conversation among some students in my homeroom about one such teacher. She was quite popular among students. “Oh, she is so nice!” “Yeah, she’s the BEST.” “I love her!!”

And then Jonathan piped up, “Yeah, I really like her too….but I don’t think we learned that much in her class.”

The kids exchanged looks. No one said anything for a few minutes. Then one of them said, “yeah, I guess you’re right.” Another pause. “But she’s so nice!”

When I was a new teacher in my twenties and looked like the 16 year olds I was teaching, I worked hard to create a persona of a demanding teacher that was a little scary. The demanding part worked, but I couldn’t pull off the scary. Aside from the fact that I looked too young to be scary, it just wasn’t me. I actually am nice. And occasionally funny (the bar is low in a classroom).

Years later, no longer looking like a 16 year old and now teaching middle schoolers, I realized it was totally fine to smile before Christmas.

Think about your favorite teachers. What was it about those teachers that made them your favorite? And is there a difference between the ones you liked and the ones you learned from? When I think back to my favorite teachers, they were all funny, nice once you got to know them AND they knew their stuff.

As nice as teachers can be, they are not as nice as your friends or your favorite babysitter. And even the funniest ones are not as funny as comedians. If they were, they’d be comedians. But they’re not. They are teachers.2 And teachers are supposed to teach. If they don’t, then what is the point? On the first day of school and on the last (and on the day before winter break), our job as teachers is to teach students something. Preferably, things that matter and in ways that are interesting and get students to learn.

The Importance of Knowledge

We cannot get students excited about learning history or math or science unless we are excited about history or math or science. A lesson can be student-centered, full of innovative technology and inspired by the latest new thing in education, but if it isn’t about something then what purpose does it serve?

I don't think enough administrators, school reformers, politicians or even teachers realize how integral content is to great teaching. With so much emphasis on using technology, debunked theories like learning styles, standards, SEL, and “21st century skills,” sometimes the most basic things are forgotten— reading, writing, thinking.3

I am a history teacher. I want my students to read, write and think about history. So….

An announcement!

I recently reached the 500 subscriber mark on Substack. Thank you to all of who have subscribed, and a special thanks to those who have recommended/liked/commented on my posts. I wouldn’t be at 500 subscribers were it not for

’s Minding the Gap or ’s The Next 30 Years.This week I am “launching” a new section of this Substack: one especially for those who teach U.S. history. While it will be geared for those who teach middle or high school level history, perhaps some others might find it of interest. Or spread the word to those who do. And if not, well, you can skip these future posts.

I’m calling it the “U.S. History Teachers’ Lounge”— a space for teachers who care about getting it right. A place where I will discuss some of the methodological, pedagogical and historiographical problems faced by teachers of U.S. history. In other words, the kinds of issues that come up when history teachers get together and talk shop in the teacher’s lounge.

There will be samples of things I’ve used in the classroom (links to real material used by real students)—examples of essential questions, document-based questions (DBQs), primary and secondary source materials. I’ll share lesson ideas that may not be fully developed with the hope that, through the comments, others might contribute ideas. They’ll be honest talk about the real struggles to teach material that is controversial, or disturbing in professional and age-appropriate ways. I’ll provide links to websites or references to books and articles where teachers can find additional material.

What this new section will not do:

It will not be a substitute for the kind of broad and deep reading of history that must be the foundation for a thoughtful practitioner.

I learned how important that is from a great history teacher: my dear friend, mentor and former department chair, James Pyne. There were four of us he hired my first year. I was the youngest and least well read of the bunch. But I spent many an hour in the library to change that, reading the articles and chapters of books he would photocopy and leave in my mailbox and the books he recommended.

On my last post about teaching as craft, I referenced a comment Pyne had once made to me about how it takes an entire career to come up with 180 great lessons. I hadn’t gotten what he meant quite right in my post, and so he corrected me in the comments. He had meant that in order to teach American history, teachers must be “well and deeply read,” so they are attune to “subtlety and nuance, acquainted with conflicting interpretations on controversial issues that professionals grapple with.”

He continued:

I must model for my students a respect for knowledge by being knowledgeable myself. All of that requires that I read, read, read. We are, we teachers, people of the book. Teaching, and the excellence that may come, begins in the library, whether brick and mortar or digital. Be wary of those who would have you become technicians in the classroom, devoted to methodology at the expense of knowledge.

I may offer techniques. I will discuss methodology. But nothing I will share can substitute for actually knowing something about U.S. history.

When I think about all the lessons I’ve created over the years, the best ones—the ones that really landed—came from deep reading: a great article, a book I couldn’t put down, sometimes a whole college syllabus’ worth of ideas. And the ones that didn’t quite work? The answer to making it work can probably found on the pages of a book I haven’t yet.

As my mentor James Pyne reminds me, we are people of the book. That’s where good teaching begins. And if we’re doing it right—if we know our stuff and care deeply about it—we just might help students catch a glimpse of something more.

Truth and beauty.

As I’ve been writing this post, I got involved in a discussion on social media about memorization and learning. Alas, whatever I once knew about chemistry from high school (I got an A in that class) I have forgotten. So, you could make the argument that I never learned it. This is way too big of an issue for either this post or a footnote. You can read a bit about learning theory on this post on Carl Hendrick’s The Learning Dispatch. But it’s something I’m thinking about and will be writing more about soon. (Stay tuned for Part II of What I learned about learning from learning Spanish. Part I is here.) Discussion on social media was about a episode I was on of Bill Davidson’s Centering the Pendulum podcast. On it, Bill ad I spoke about an article I wrote for MiddleWeb about having my 7th graders memorize the 50 states and what I learned from that experience. I also wrote a companion piece about using math in history class.

Okay, so some teachers are also working as comedians. Check out https://www.chicagotribune.com/2025/02/19/from-classroom-to-stand-up-comedy-teachers-take-to-the-stage/

For more on this, see an article I wrote for MiddleWeb in August of 2020, “Balancing Content and SEL as School Begins.” Obviously, it was written as I planned to start the pandemic school year teaching on Zoom. But in many ways, the same thoughts still apply.

I’m looking forward to reading U.S. History Teachers’ Lounge! I’m currently reorganizing all of my US History resources for next year, pruning what I haven’t used in years and adding more.