What I'm learning about READING from learning Spanish: Part I

Thoughts from a history teacher about reading

Since October, I’ve been reading weekly with Ana, a 4th grader from Venezuela who’s new to the U.S.1 Because her English is quite limited, we read in Spanish—her first language and one that I’m currently studying—which has made for some surprising discoveries.

A few weeks ago, we were reading a graphic novel version of El Club de Las Baby-Sitters. We took turns reading, and here’s what I noticed.

Her pronunciation was way better than mine. Duh. No one listening to me read would mistake me for a native speaker of Spanish.

Surprisingly, however, I could read faster than she could. Though a native-born Spanish speaker, her reading was not as quick as mine. I could decode faster. While I occasionally stumbled on multisyllabic words, so did she. While no one would mistake me for a native speaker, my fluency in reading and my accent could lead someone to assume my Spanish is way better than it actually is. Which makes these next points quite interesting:

She understood the reading, and I did not. Even when I recognized 90% of the individual words in a sentence, I often couldn’t put the meaning together quickly enough before it was time to read or listen to the next sentence. I might be reasonably fluid in decoding, but I’m way slower when it comes to the speed at which I can comprehend. The cognitive load of decoding, pronouncing words accurately with a decent accent and discerning meaning all at the same time is too heavy.

Because of #3, I understood it better when Ana was reading than when I was. When she was reading, my cognitive load was much lighter, and so I could devote more attention to comprehension.

On days when Ana wants me to read the whole time, I am mentally exhausted at the end of 40 minutes.

Reading Stamina

This led to an “aha” moment, thinking about my 8th graders’ struggles with reading stamina.

I recall an incident from a few years back but post-Covid. I had given my 8th graders a reading on the Great Depression. It was printed on three pages with quite a few illustrations, including one that took up nearly half of the second page and the third page only had one (!) paragraph of text on it, followed by a few questions to answer. When I finally got the class settled down and reading, Mila raised her hand and called me over to her desk.

Mila (looking concerned and even a bit shocked): Ms. Brown, do we have to read this?

Me (somewhat surprised, but trying not to show it): …yes.

Mila flips through the three pages, her facial expression demonstrating her trepidation at having to read so much.

Mila: All of it?

Me (trying to mask my continued surprise and instead aiming for a gentle tone that would also demonstrate confidence in her ability to do it): Yes. It will help you with the questions, and a future assignment. Once you get started, I think you’ll find it interesting.

Mila sighs and begins reading.

I remember puzzling over that exchange for a long time. I mean, sure, I’ve been teaching for nearly 20 years, so students complaining about reading is nothing new. But this felt different. Mila didn’t seem annoyed or lazy. There was no eye-roll or groan; she seemed genuinely shocked that she was being asked to read at all.

I shared the anecdote with other teachers, asking them if they were noticing the same thing about our students’ increasing reluctance to read. “Yeah,” they would reply. “It’s like they just don’t have the stamina for it after COVID.” My friends who taught high school and college were noticing the same thing. And the popular press has definitely picked up on it.2

One of the things I found confusing at the time was that Mila was a competent reader. However much she didn’t want to read about the Great Depression, I knew that if she read it, she would understand most of it. Certainly more than I understood from reading El Club de Las Baby-Sitters.

But what I’m realizing now is that one or maybe both of the following might be true:

While Mila could read—much better than I can read Spanish— maybe she didn’t read as well as her reading test scores suggested.

Or maybe she could read well—just like I can decode Spanish pretty well and sound like I’m more fluent than I am— but reading something that long and answering questions is hard work. I was the one who put the reading together and came up with the questions, and I’ve been teaching about the Depression for years and know a lot about it, so it doesn’t seem that hard to me. But I am not Mila.

I can see more clearly how demanding reading can feel, even for competent readers—when decoding and meaning-making don’t come easily. And that brings me back to Ana, and to me, struggling through El Club de Las Baby-Sitters, where vocabulary becomes its own kind of obstacle.

Vocabulary

When I try to understand El Club de Las Baby-Sitters, I’m constantly tripped up by unfamiliar words. For example, I read that Kristy’s mom is going to—wait, what is this?—casar (to marry)? If the text had said la boda (wedding), I would’ve understood, but I didn’t know the verb casar, so I missed the meaning entirely.

Not knowing a single word can make an entire passage incomprehensible. I remember one of my 8th graders struggling with an activity on the 1930s refugee crisis for European Jews. I had given students a set of cards with text, quotes, graphs, charts, and maps. Their task was to sort the cards into categories that explained why the U.S. didn’t rush to accept Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. The categories included: “antisemitism,” “financial issues/still a Depression going on,” and “competing concerns or other issues considered more important.” Students were told that cards could fit under more than one heading.

Here is one of the cards:

I thought this was an easy one (financial issues/still a Depression going on), until one of my students came up to me and asked me what a “public charge” was. After another student came up and asked me the same thing, I explained it to the class and heard a few kids say, “oh!” and reach for that card.

Since then, I have added the phrase “need $ or other support from government” to the card, removing the vocabulary barrier. But I learned valuable lessons from the student’s question. First, teachers don’t always know what words their students don’t know. Second, only two students came up to ask. Cleary, other students didn’t know the word either. Some students are embarrassed to ask questions, assuming everyone else knows it and they don’t.

Over the years, I’ve come across other words that I didn’t realize my 8th graders didn’t know. Here are a few:

Some of them are less surprising than others (e.g: paternalistic, annex/annexation). Some take on added meaning when used in the context of U.S. history (moderate, radical, or others I didn’t list above like liberal/liberalism and conservative/ conservatism). Sometimes kids know the word but haven’t come across it in print or didn’t realize there were other meanings of the word. I can imagine most 8th graders have encountered “erosion” in science class but used as a verb in a sentence like “The Great Depression caused many people’s trust in the government to erode” might confuse them. Or they know the word “profit” but adding “ability” onto it trips them up.

Or take a word like “legislate.” In a district where students have to pass a Constitution test in 7th grade, most of my 8th graders easily recall that “the legislative branch makes the laws.” But with all there is to learn about the Constitution, I know that when I taught 7th grade, I didn’t take the time to explain the etymology of the word— that“legislative” comes from the Latin word lex meaning law and that “to legislate” means to make laws and the legislature is the body that legislates. Nor did I explain that “legislative” is the adjective and that it shares a root with the word “legal.”3

Every teacher struggles with how much there is to teach and how little time there is. There never feels like there is enough time to “cover” everything. So making careful use of our time is critical.

Morphemes & Etymology: Breadth and Depth of Vocabulary

I sacrificed the etymology of legislative to get to other things. But what I’m learning from studying Spanish is that it takes a lot of time and multiple exposures to a word in order to move it from recognition (when I see it in print or hear it) to being able to produce it myself in speech or writing. I have probably been exposed to thousands of words in Spanish, but the number of words I actually know — that is, words that I could use correctly in a sentence or read without having to use a dictionary or Google translate is far smaller.

So we need to make more time for things like etymology and also morphemes in our lessons. In a way, etymology and morphemes can be used as shortcuts to learning more words and making them stick. Once I realized some of my students didn’t know the word import and export, I referenced the morphemes “ex” (exit, exhale) and “im” (immigrant, implant) in my explanation to make it easier to learn. Learning the meaning of e pluribus unum, a phrase on our national currency, is easier if can connect it to words like “plural” or “unique” or “uno,” a Spanish word my 8th graders all know whether or not they are taking Spanish.

Because I love to eat, the words I know best in Spanish have to do with food and cooking. I first looked up the word salteado (sauteed) when reading a menu in Mexico. I’ve read enough menus now that I no longer need to look it up if I see it in the context of a menu or recipe. I can also recognize the verb, to sauté (saltear), if I saw it in a cookbook. But if I was speaking, without the word in front of me, I might easily say saltar instead of saltear.

Until….

I learned that the word saltear literally means to jump around in the pan, which is what happens when you sauté something. And that saltar is the Spanish word for jump. And this is same thing in French (sauter = to jump, and of course the English word “sauté” actually is a French word). This new depth of the word salteado will help me with breadth— I’m hopeful that the verb saltar might have moved into my longterm memory, where it has cozied up to salteado.

You can read more about depth and breath of vocabulary below.4

Reading at one’s level

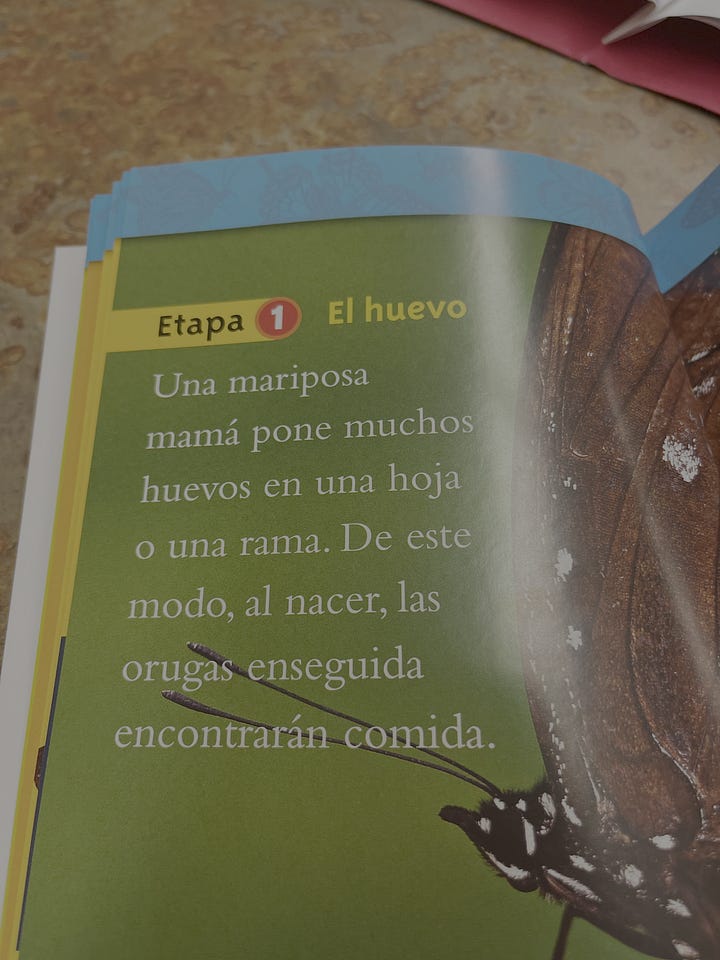

Last week with Ana, the book choices in Spanish were limited. No chapter books except for one on the World Cup which she rejected (soccer isn’t her thing). So we read De La Oruga a la Mariposa, the Spanish edition of Caterpillar to Butterfly from National Geographic Kids.

On the page above (right), we both struggled with the word enseguida (immediately). She struggled with decoding the word; I could decode it easily but didn’t know what it meant.

Overall, it was a much easier book for me to understand— a level 1 reader with a Lexile score of 470 making it at a pre-K/Kindergarten level. But Ana didn’t like it; it was babyish and boring. She wants stories that challenge and interest her. Reading aloud from harder texts helps her engage and grow, even if she can’t decode everything yet. When we read a book like El Club de Las Baby-Sitters, she is interested.

Reading aloud to students from texts that are more advanced is so important for building knowledge and exposing them to new vocabulary and more advanced syntax. I am hardly the first to point this out.5 Ana might struggle to read El Club de Las Baby-Sitters on her own, but she understands and enjoys the book.

Tomorrow, we’ll try to find something more interesting than caterpillars. In the meantime, I’m stepping up my Spanish learning with some new color-coded flashcards and better ideas on how to use them.

So stay tuned for Part II of this post: What I'm learning about LEARNING from learning Spanish.

Name has been changed to protect her privacy. Same with the student, Mila, discussed later in this article.

See for example, the widely hyped article from Rose Horowitch in The Atlantic, “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” and check out this Substack post from one of the high school teachers that was interviewed for the article. It offers more nuance and takes issue with some of Horowitch’s points.

Also, see two English teachers take on the article (short answer: they find flaws in the article, but admit that kids aren’t reading as much as they probably should.

This is why we need more social studies (and science) in grade school. If we want our students to understand civics, we need to start earlier than 7th grade. Vocabulary related to the word “legislature” can be taught at the elementary level. Check out minute 43:00 (approximately) in this webinar from Knowledge Matters about vocabulary. Fifth grade teacher Sean Morrissey talks about morphology and teaching students roots like the Greek roots “arch” meaning rule (monarchy, oligarchy), demos meaning people (democracy, demonstrate) and the Latin root civis meaning citizen (civilization, civic). He offers this as a strategy for middle school teachers but I would bet a lot of money that you could do some of this even earlier, depending on the words. As Sean points out earlier (about minute 24:40), to learn vocabulary well, students need repeated exposure to words in order to know them.

See this article from Five from Five, an Australian education initiative designed to improve literacy using evidence-based reading instruction.

For starters, check out minute 44:00 in the webinar mentioned in the footnote above. Here, literacy researcher Sonia Cabell from Florida State University explains (in about 2 minutes) how reading aloud helps students learn words they will not encounter in day-to-day life but that are important for building literacy. I highly recommend the entire webinar.

thank you for sharing this. I really enjoyed the information shared and found immense value in it from a instructional perspective. Keep up the great work Lauren!!!!

I'm starting to convince myself that cognitive load theory explains the vast majority of issues we see in the classroom.