You can read Part I of this post here, but you don’t have to in order to get something out of this one. It’s about the difference between learning something and actually knowing it.

I have been dabbling in studying Spanish for years now. Every now and then I am able to carve out some time to take a class and a couple of times I’ve even been able to do a week-long intensive class in Mexico. But then summer is over, I go back to school, and I forget.

This year, I carved out time to take a A2 level Spanish conversation class once a week.1 It combines a little bit of grammar with a lot of conversation. I’m convinced that my Spanish is the worst of my classmates. This is because sometimes the teacher will say something and everyone else will laugh. So I just kinda nod and smile.

I have, though, learned a lot of Spanish over the years, even before taking this class. When I looked at this big long list of things one learns in level A-2, I realized I have at some point, learned probably 85% of this.

Learning vs. knowing, concocer vs. saber

But here’s the rub: there is a world of difference between learning something and actually knowing it. I can conjugate verbs in both the preterite and imperfect tenses and understand when to use, but before I do it, I have to ask myself a series of questions (is it a completed action? ongoing? descriptive?) and then whether the verb is -ar, -er, -ir or irregular and that’s a lot to process.

I know the word for window, cheerful and butter. Except for when I forget them because I haven’t used those words in awhile. I know the adverbs a, en, para and por but mix them up constantly. Do I live en or a Chicago?

I know the difference between the two verbs that mean to know: conocer and saber. Generally, the former is used for being acquainted with something:

Do you know Emma?

Do you know this restaurant?

Do you know that movie?

While saber is the one to use when you know something more thoroughly or know a fact:

Do you know Spanish?

Do you know how to solve for X?

Do you know what caused the Great Depression?

Do you know the meaning of life?2

In a way, these two verbs are a metaphor for learning. Being familiar with something just isn’t the same as actually knowing it.

This is abundantly clear when I volunteer to read with Ana, a 4th grader from Venezuela, who I wrote about in Part I of this post. We speak in Spanish because she speaks far less English than I do Spanish. But unlike my Spanish teacher, who is trained to speak slowly, enunciate clearly, use synonyms and repeat things so we can understand, Ana just talks to me like a regular person. This means she speaks quickly and sometimes mumbles (in a room filled with other 4th graders to boot), so I must constantly ask her to slow down or say it again. And then, when I finally realize she is asking me something simple—do you live close to this school?— I can answer, si, vivo cerca. But I can’t say 4 blocks because I forgot the word for “blocks.” I draw a square in the air. She smiles, “4 cuadras.”

Drat, I think to myself. I knew that word. Cuadras.

But did I know the word? It’s like my students when they get something wrong on a test…oh, but I knew that, they say.

What does it mean to know something?

I’m not going to pretend I can answer that; I am neither a philosopher of epistemology nor a cognitive scientist, though I’ve been reading a lot about the latter lately. I will say that it’s a foundational question: I tend to go on and on in other posts about how important it is for students to know things. But what does that actually look like in a classroom? And how do we know if our students know the things we want them to learn?

Any teacher whose students have asked if the test will be multiple choice or essay knows that recognition is different from recalling. For one thing, it’s easier.3 I recognize the word cuadras, and if I read or hear it in context—“She lives four cuadras (blocks) away from the school, so she can walk” I will understand its meaning. But to produce the word on my own I resort to drawing a little square in the air.

Blake Harvard, known here on Substack as @effortfuleduktr, has written a widely-hyped-for-good-reason new book, Do I Have Your Attention? Understanding Memory Constraints and Maximizing Learning.4 In the chapter on retrieval practice, he offers a teaching technique he calls “Brain-Book-Buddy” which is a pretty genius way to help our students appreciate how we all delude ourselves about how much we actually know, whether it’s Spanish or studying for a test in school. It involves having students take a practice quiz using just their brain, then they get to use their notebooks to see if their notes “knew” the answers, and then they get to talk to a friend and see if their friend had the notes but they didn’t. See this footnote to learn more.5

Retrieval practice

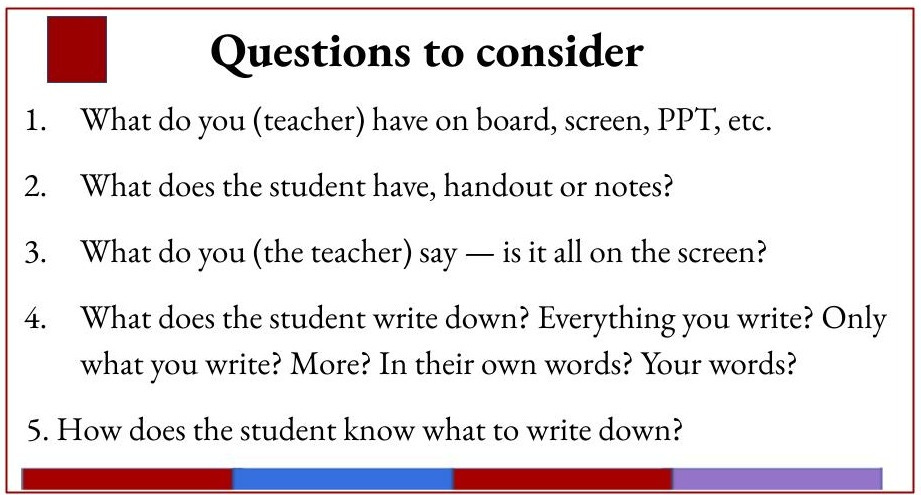

This is why taking notes in class is not just some old-fashioned relic of a bygone age. Writing things down is one of the things we can do to get something from sensory memory to working memory to long term memory, where we can use it if we want to say we live four blocks away. Of course, merely copying down notes from a teacher’s slides is a terribly ineffective way to do that. That’s why I share the graphic below with my preservice teachers.

So when we do have students take notes from slides, we must remember that is just a first step. We need to teach students how to take notes— putting information in their own words so they are processing information and not just copying it down. That’s why sometimes in class I’ll just pause and ask students to take a few minutes to discuss with a partner or summarize what we just discussed. Students also have to do things with their notes and write things other than just notes, such as responses to questions and summaries of readings or other materials. This is what moves the learning into knowing.

My epiphany: putting all this together

So one day in Spanish class, frustrated by the realization that I was not magically fluent yet, and dejectedly comparing myself to Joe, clearly the best speaker in our class, I had the epiphany. I was just like my students who maybe took some notes in class and then put them away and went on with their day, their week, the rest of the unit, never looking at the notes again and then wondered why they didn’t do well on the test.

So what was Joe doing over there at the other end of the table with all those colored flashcards on rings? He was delighted to explain his method to me. He used different colored flashcards for different parts of speech: blue for nouns, green for verbs, yellow for adjectives and adverbs, and orange for expressions or other things. At home, he picks a card from each color group and makes up sentences using the words. Sometimes he just picks a verb and conjugates it in the present tense, then he takes a second verb and conjugates in the past tense, and so on.

In other words, retrieval practice. Maybe it’s just a fancy way of saying “studying,” but more and more, I’m realizing it’s not. “Studying” is when we look through or notes or flashcards and fool ourselves into thinking we’re learning the material. Making sentences with the individual words is actually using the knowledge. It’s why I tell my students don’t just read through your notes when you’re studying. Read them out loud. And then put them down and see if you can explain it out loud to yourself in your own words. Discuss the material with a friend. Use your notes to answer the essential questions of the unit.

Clearly, one class of Spanish a week is not going to get me to level B-1 Spanish.

It’s time….

I got myself some flashcards.

If you want to know what an A2 level speaker sounds like, check out this video to hear someone at an A2 level in English. It’s a sobering experience for me to listen to this, because in my head, I’m a way better speaker than that. But the truth is, to someone fluent in Spanish, this is what I sound like. Sigh. (And no insult intended to the English learner in this video! English is a maddeningly difficult and harder than Spanish because it is not phonetic.)

Actually, this was a very amusing task: asking Google Translate a bunch of questions, despite the fact that it is not the best translator out there. For example, I asked it to translate, “Do you know the causes of World War I?” And I got conocer. When I changed causes to singular—cause—I got saber. Same with the Great Depression.“Do you know your multiplication tables” gave me conocer. “Do you know what 5X3 equals?” gave me saber. When I asked it “Do you know the capital of Venezuela?” it used conocer, which I didn’t think was correct, so I changed it to “Do you know what is the capital of Venezuela and then I got saber. I think Google Translate was thinking it was “are you familiar with the capital of Venezuela,” as in hey, you ever been to Caracas and know some good restaurants? So perhaps this is all more complicated, but then again, you’re not reading this article to learn about the Spanish language, but about education issues. Though honestly, this is an education issue. Ask any foreign language teacher you know about how irritating it is when their students just use Google translate. I know enough Spanish (I think?) to know what to enter into Google translate to get the right translation. Just like what we enter into any search engine or AI—the more we know about a subject, the better quality search we will get.

Although that does not always translate into higher grades on multiple choice tests vs. essay tests. But that’s a whole other discussion.

On p. 77 of that book Harvard talks about the difference between recognition and recall, and confirms what I said about multiple choice vs. essay tests. He also has his own Substack newsletter, blog and is all over social media, including this recent article from The 74 and Jennifer Gonzalez’s Cult of Pedagogy podcast.

It’s described on pages 81-84, which an additional twist, “Did you guess?” on pp. 84-89. You can also hear Blake Harvard describe the method on Zach Groshell’s Progressively Incorrect podcast at about minute 16:25.