The power of reading aloud in history class

Why we should do it and what we should read

I first started reading aloud to my high school students because I liked it and they seemed to enjoy it. Also for practical reasons: too many students don’t do homework and I wanted to make sure that certain things were actually read.

Since then, I have learned there is considerable research that supports this practice. Here are the 2 major conclusions from some of what I’ve read on that:

Students comprehend reading that might be above their reading level if it is read aloud. When students have to carry the cognitive load of reading (vs. listening and following along in the text), it can be harder for them to get the meaning. Or enjoy it.

Reading aloud creates an experience and builds community. Human beings developed oral language long before the written word. Hearing a story is a different experience from reading it. We think about reading aloud as something reserved for children– kids on the carpet in grade school or snuggled on the couch with a parent. If that were true, audio books wouldn’t be so popular.

Reading aloud is powerful

Here are a few other reasons to read aloud, based on my experience as a teacher.1

It sends a powerful message that reading history is interesting. (Assuming you pick something that is actually interesting!)

When I read an excerpt from a book I’ve read, I become a role model: someone who reads and continues to learn new things from reading.2

It might encourage some students to read more. I’ll leave a book hanging around on my desk for a week, and there’s always a handful of students who will pick it up and flip through it or grab a post-it and write down the title.

What about having the students read aloud instead of the teacher? Don’t teachers talk too much already? Shouldn’t students be doing the “work” of reading?

First of all, just because I sometimes read aloud doesn’t mean that students never read for themselves. There is a time and place for that kind of classroom reading, but consider potential drawbacks:

It can be awkward or embarrassing for poor readers or English language learners. Obviously, kids need to work on fluency skills. But when the objective is comprehension of the text, you need strong readers.

Even strong readers, when reading something they haven’t practiced, might not put the emphasis in the right place.3 Especially if the reading is a narrative (fiction or nonfiction), it will be read better by someone who has read it in advance. It is not as enjoyable or effective for students to hear a peer reading too fast, too slow or in a monotone or stumbling over challenging words.

I will repeat: students can comprehend reading that is above their actual reading ability when read aloud. But they still need help. If I’m the one reading, it is less intrusive to interject commentary, like defining a word, than it would be to interrupt a student.

Switching from student to student interrupts the flow and breaks concentration. “Wait, what page are we on?” And then we all wait while Ivan shows Jenna what page and what paragraph we are reading and then Ellie starts laughing and then Jenna gets annoyed and then….you get it.4

What should history teachers read to their students?

Alright, hopefully now you are convinced that reading aloud, even for middle and high schoolers might be worth a try. So what should you read to them?

For starters, read the famous stuff: the speeches that were originally consumed by listening not reading. The Gettysburg Address, Lincoln's 2nd Inaugural Address, Wilson's War Message to Congress, F.D.R's inaugural address—you get the idea and probably already do that.

So what other kinds of things can you read aloud?

Excerpts from actual history books

This also sends an important message to students, one that they need to hear: your history teacher reads history books. And, surprise, surprise, most history books are far better written than textbooks.5 Many books are complex and too challenging for the average high school or middle school student to read on their own, but not too complex to understand.

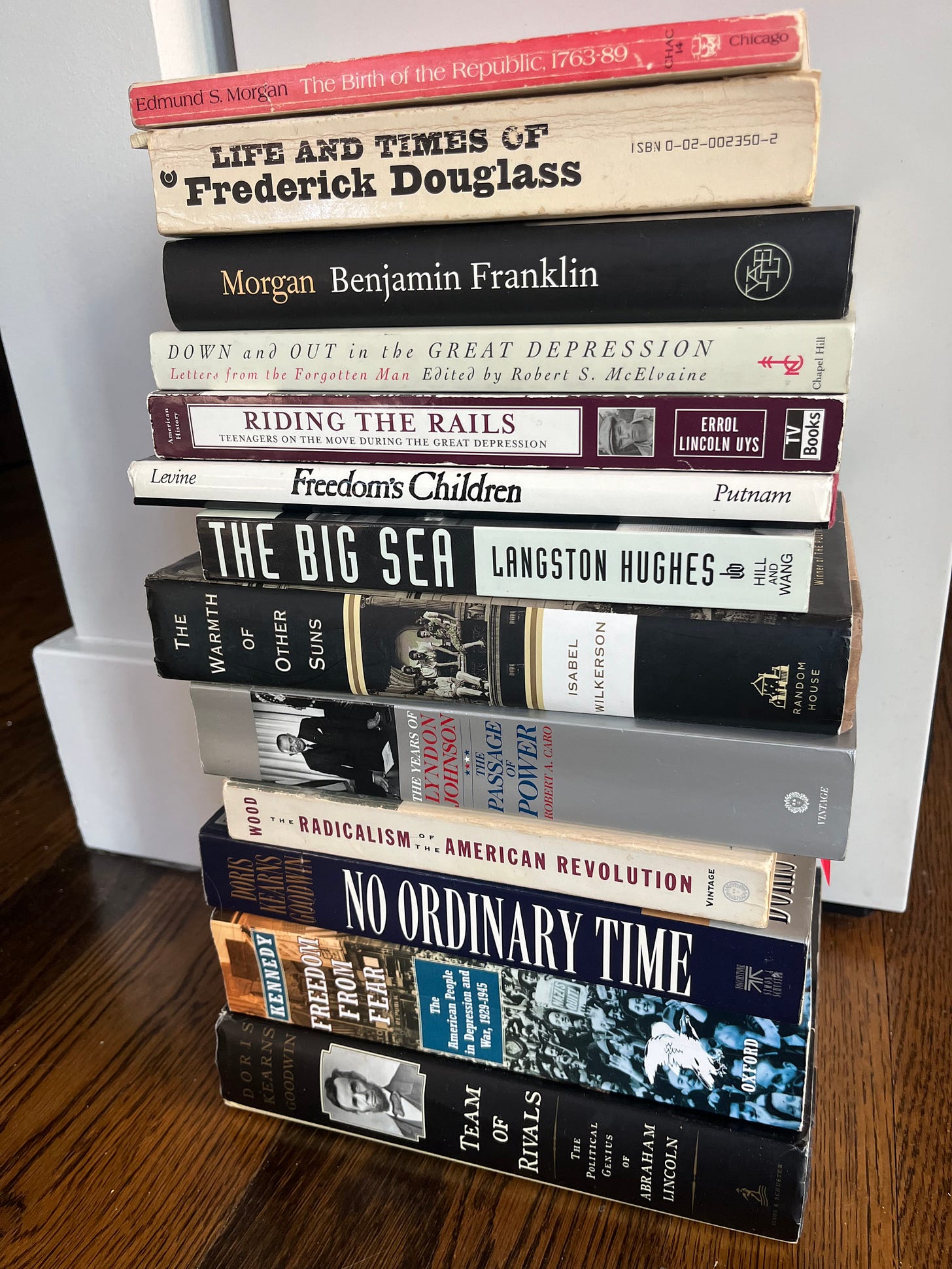

Reading even just a paragraph or a page or two adds to the content quality of what you are teaching. Check out the paragraph below that I used with my 7th graders in a lesson about how the colonies became used to doing their own thing long before they declared independence. It’s from an old classic by Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763-1789.

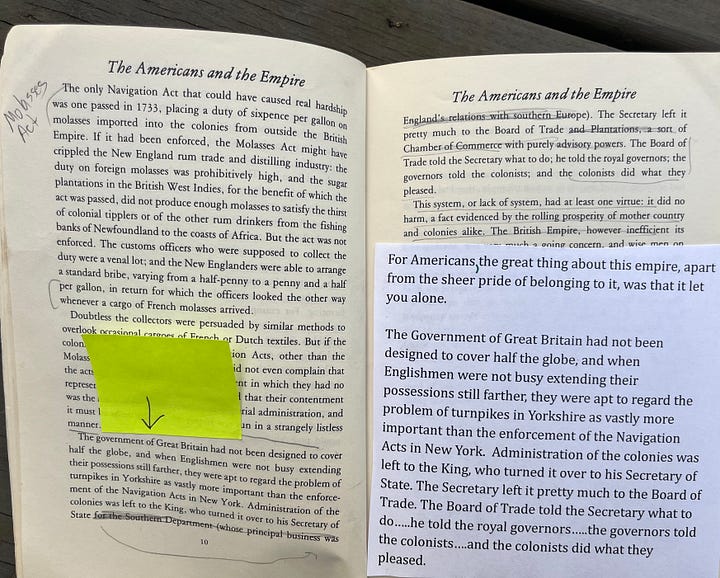

The Government of Great Britain had not been designed to cover half the globe, and when Englishmen were not busy extending their possessions still farther, they were apt to regard the problem of turnpikes in Yorkshire as vastly more important than the enforcement of the Navigation Acts in New York. Administration of the colonies was left to the King, who turned it over to his Secretary of State for the Southern Department (whose principal business was England’s relations with southern Europe.) The Secretary left it pretty much to the Board of Trade and Plantations, a sort of Chamber of Commerce with purely advisory powers. The Board of Trade told the Secretary what to do; he told the royal governors; the governors told the colonists; and the colonists did what they pleased.

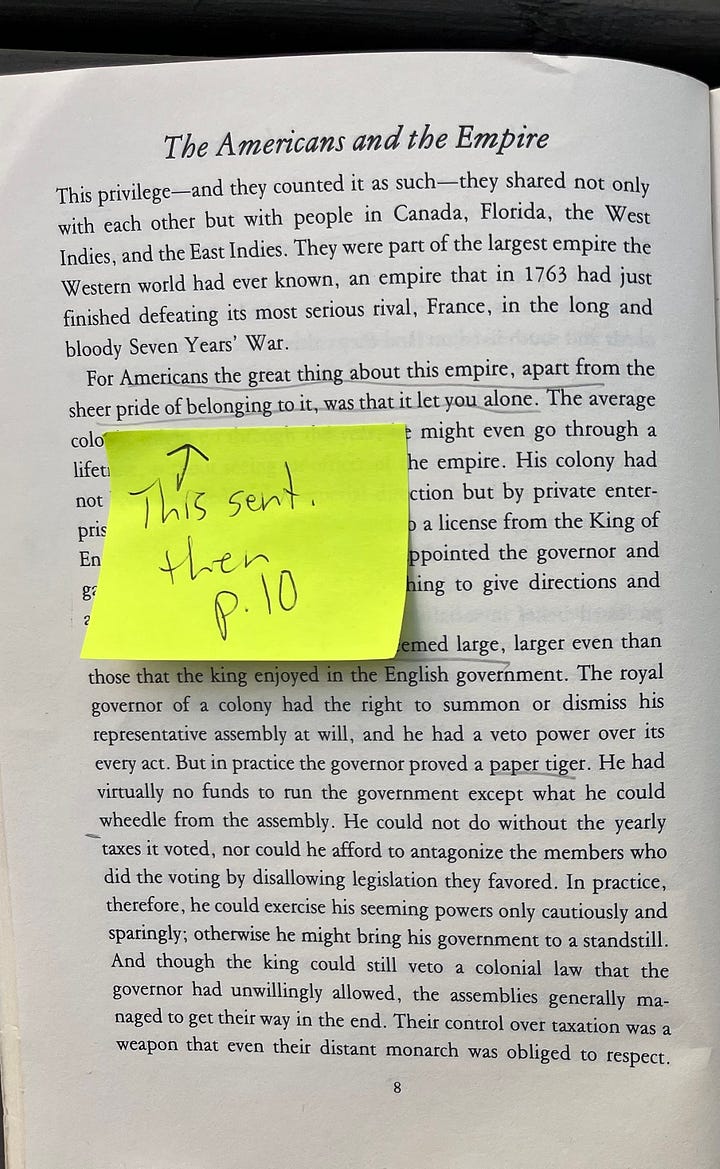

Because it’s funny, right? And even with words like “apt” and “administration” that might be hard for middle schoolers, they will get it if you read it aloud. When I used it, I made a few edits. I added a sentence from page 8 and cut a few cumbersome phrases. And then, because now I need reading glasses, I actually retyped the passage with the edits, changed the punctuation to help me know when to pause and actually taped it inside the book!

Why? Because I like to read from the ACTUAL BOOK, not a photocopy of the page or pages to emphasize the point that books matter. Even if the students have a photocopy, and I’ve edited it, I will read from the actual book. And, LOL, this is what my book looks like:

Is editing like that cheating?

No! It’s an excerpt! Tell them it’s an excerpt. Just as you may give students an edited version of a text to read for themselves, you can edit what you read aloud. Read it out loud to yourself before you read it in class and you will know if you can cut a particular paragraph or phrase because it sounds clunky or slows things down too much. If students are following along with their own copy, just note it.

Reading things that are troubling: All Quiet on the Western Front

In my 8th grade World War I unit, we used to read chapter 6 of All Quiet on the Western Front. There were a few parts that I felt were too disturbing to read aloud. They each had a copy of the entire book, so they could see what I was skipping. I had told them in advance why I was skipping it, and let them know that if they wanted to read those few pages they certainly could. I just didn't want to subject more sensitive students to those parts and again, hearing something out loud is a different experience than reading it to yourself. (Of course, if it is age-inappropriate you can’t let them do that.)

My objective in reading the chapter was to show the horror and drudgery of war. There was plenty of that without reading every single page. Not to mention the perennial problem of time. I did spend three 40 minute class periods on that book, which is a lot, grueling even.6 And so we paused often to do a bit of writing and discuss. One of the things we discussed, which I brought up strategically at the first signs of fading interest, was that the point of the chapter (and the whole book) is that war is hell. Or as the old saying goes,7 “war is long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.” We discussed the merits of reading something that was painful and dreary for so many minutes, and that was a “teachable moment.” Furthermore, it refreshed their commitment to paying attention, because now the very act of listening to this reading was honoring fallen soldiers. (Okay, maybe I’m exaggerating here, but in the reflections they later wrote, an awful lot of them wrote that even if they didn’t exactly enjoy the reading, they thought it was important and were glad to have heard it.)8

So maybe now you are wondering…

If I teach 3 sections of a class, that’s an awful lot of reading….

Yep, this is the downside. Drink lots of water and have throat lozenges handy. Plan ahead of time to do something where you won’t have to talk the next day or for your other classes, if you teach other subjects. And don’t forget to build in discussion and writing time that have the dual function of allowing you a break.

Or: invite someone else in to read! What an opportunity to invite an administrator or the librarian or a parent. Just make sure they are good readers and give them the text in advance with some context (e.g. why you have chosen this text; the objectives, etc.).

Another alternative: use an audio book recording. While it might lack the immediacy of a live reader, there are merits to hired professionals.

Of course, another option is to pick student volunteers in advance. You know who the strong and eager readers are, and they might welcome this opportunity. I did this quite successfully my 11th graders, using excerpts from Ellen Levine, Freedom's Children: Young Civil Rights Activists Tell Their Own Stories. It’s soooo good. I actually prefer having a student read this because they are stories of young people.

Some other examples I have successfully used in my classroom:

Chapter 9 of Uncle Tom's Cabin. I have to admit I was surprised at how well this worked with 7th graders, given the dated language and how old-fashioned it sounds. Of course, part of that was the point—see my note about question #7 on the discussion questions I used.

As Uncle Tom's Cabin was to the Civil War, Upton Sinclair's The Jungle was to the Progressive Era. What teacher doesn't read this aloud, right? The part about the rat droppings. I use the 2nd excerpt on this PDF which is from Chapter 14.

Excerpts from Frederick Douglass's Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass have also worked well with both high school and middle school students of mine. I especially like the part about he learns to read and write. You can find that in chapter 6 here (but note use of the n-word; personally, I would redact that word.)

1920s: Check out Me and My Flapper Daughters - the link is to my edited version. I used this with high school students; a little PG-13 for middle school, I think.

World War II: Dr. Seuss, “Yertle the Turtle” - I have sometimes read this storybook style, asking my too-big-to-sit-cross-legged students to try it anyway and gather round so they can see the picture. They have little trouble seeing the connection to totalitarianism. If you have students who ask whether or not Dr. Seuss has been “canceled” make sure you check out the footnote here.9

D-Day: Stephen E. Ambrose, D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climatic Battle of World War II- the very beginning of the Prologue tells a good story about Lt. Den Brotheridge who is the first soldier to be killed on D-Day. It’s a great way to get students to empathize with the soldiers as people before going on to study the facts about D-Day.

How can I find other examples?

As you read, whether for school or for pleasure, be on the lookout for excerpts that would work for your students. Use post-it notes and write page numbers in the back of books to note possible excerpts, like I did in the picture below.

You gotta read to find stuff to read. Hopefully, many of you have, and will leave some suggestions in the comments!

What to look for in a good read-aloud

Biographical accounts are especially good for read-alouds because they are written in order to bring a person to life. Reading a short section from a biography— a description of an early life-changing moment, or a few paragraphs that offer a rich description of appearance and personality (with a photo or painting displayed at the same time) would work well.

Excerpts that are descriptive or tell a story are the key things to look for— the details that draw in our students and remind them that history is the story of actual people. People who had mothers and fathers and maybe siblings and likely once went to school themselves. It’s the stories that make history come alive. We can read those stories to our students.

A note about a research. I’m a teacher, not a researcher, so all I can give you is anecdotal evidence based on my nearly 20 years in the classroom and what I’ve taken away from reading some of the research. The academically-minded me wants to cite sources and provide evidence. It’s absolutely there. But the human me that is writing this Substack for free realizes that providing those resources takes a LOT of time and would turn this into onerous (and again, unpaid) work for me. I have endless admiration for other Substack writers who include such citations and resources. If you are a teacher reading this, I trust that you can find the evidence yourself if you need it or try things in your classroom for yourself and see if it works. I have been using ChatGPT more and more to help me find (and summarize) the research. But I have my limits and so does ChatGPT. When I used it this morning to find something for this article, it gave me a made up quote from the educator Vivian Paley. That’s when I abandoned ship and wrote this footnote instead. But I’ll give you on

And backed by research. Here’s one research tidbit: check out John Hattie’s research about teacher credibility by starting here. For a “from a teacher” distillation of that research, check out this from Dave Stuart, Jr., a teacher/blogger/speaker. Lastly, check out p. 214 and pp. 239-248 of Reading Reconsidered: A Practical Guide to Rigorous Literacy Instruction by Doug Lemov, Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway. Or read the gist of it on Lemov’s blogpost of 3/5/25. There’s also a video clip which, though I think the teacher’s reading could be better, I LOVE what she does at minute 2:01 to explain something her students might not know. It is also a great use of alternating between students reading and the teacher.

In the New York Times article I linked to in note 1 above, Willingham gives a great example. The emphasis in the famous line from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet might be better understood with the emphasis on the name: “wherefore art thou Romeo.” Makes it easier to understand that Juliet is not asking where he is but fretting about who he is. I mean, I knew that, but I’m pretty sure that I’ve never said the line like that.

Names of students and the incident is fictional. You can read more here: What's Really Wrong with Round Robin Reading? - from the International Literacy Association. This article has links to further research if that’s your jam. Also check out 5 Teaching Practices I'm Kicking to the Curb - from Cult of Pedagogy, by Jennifer Gonzalez. One of the 5 practices she mentions is Round Robin/Popcorn reading, though the other 4 are worth reading too. See also Reading Reconsidered: A Practical Guide to Rigorous Literacy Instruction by Doug Lemov, Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway, pp. 211-238.

I rarely read aloud from the textbook because I almost never use one and they are almost always boring. There is so much else out there. For example, see Joy Hakim, A History of US, from which I do like to read aloud and/or assign or have students read aloud.

And the reason I stopped doing it. But maybe you have a big unit on World War I or teach world history, which (I would argue) is the better course in which to read that book.

To set up the novel, we also read the famous poem by Wilfred Owen, "Dulce Et Decorum Est." And rather than reading it myself, I found a video of the English actor, Christopher Eccleston, reading it aloud on youtube. Check it out; a good demonstration of the fact that sometimes professional actors are better readers than teachers. And if you are interested, here is the introductory handout I created.

In later lessons, we look at some of his political cartoons. One of the things we discuss is the problematic portrayal of the Japanese compared to the his cartoons about opportunity for African Americans in the war industry and ones that are critical of Nazism. See the two articles below. Scroll down to the end of both to read about his trip to Japan after Hiroshima and how that likely influenced Horton Hears a Who .https://www.openculture.com/2014/08/dr-seuss-draws-racist-anti-japanese-cartoons-during-ww-ii.html and a longer one: https://freshwriting.nd.edu/essays/can-we-forgive-dr-seuss/

I love everything about this! I love reading aloud to my World History 10th graders, I love using REAL books, I love hyping reading :)

I'm thinking about reading a whole book to my classes next year (maybe I MUST BETRAY YOU by Ruta Sepetys), like the last five minutes of every class period. Not for an assignment or anything, just for fun.

I completely agree on the value of reading aloud in class--including history class. But I wonder at what point we can start expecting, or requiring, students to do reading as homework, and also to read at length on their own.

I ask because lately I've been thinking about what is going on in college classrooms. As you may be aware, even professors at elite universities are saying their students can't or won't do reading assignments, at least not lengthy ones. I've spoken to several college-level instructors about this, and it does seem to be a serious issue.

I realize you're teaching middle school, not high school, but it seems to me that students need to start reading independently outside of class at some point to be equipped for college-level work. I'd love to hear your thoughts.