Responsible Patriotism: Teaching U.S. History in the Public School

A takeaway from Trump's Inaugural Address

Welcome! I'm Lauren Brown and this is my newsletter on education issues that impact all of us— parents, educators & concerned citizens. Today’s post is in reaction to a comment made by Trump in his inaugural address on Monday.

While this Substack is about education, not politics, nearly everything in education has been politicized. This is especially true when it comes to what we teach students in history class.

The quote that jumped out at me from Trump’s inauguration address on Monday struck a nerve: “we have an education system that teaches our children to be ashamed of themselves — in many cases, to hate our country despite the love that we try so desperately to provide to them.”

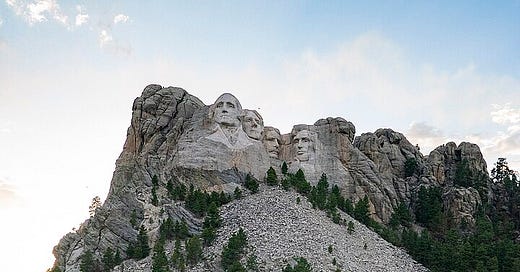

This is not a new thought from Trump. I first recall hearing it on July 3, 2020 (coincidentally my birthday) in a speech he delivered at Mount Rushmore.

“Against every law of society and nature, our children are taught in school to hate their own country, and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes, but that [they] were villains.”

In my last post, I wrote about binaries in education and the dangers of turning so many complicated issues into neat, polar opposites. So too is it with patriotism. To suggest, as Trump has, that history is about clear heroes and villains is simplistic. Ironically, he himself notes that in the very next sentence of his speech:

“The radical view of American history is a web of lies — all perspective is removed, every virtue is obscured, every motive is twisted, every fact is distorted, and every flaw is magnified until the history is purged and the record is disfigured beyond all recognition.”1

Aside from the part about the “web of lies,” his point is well taken. History, without perspective, is problematic at best, and manipulative at worst. But Trump pivots and simply makes the error from the other side. He doesn’t want teachers to magnify flaws, but what about magnifying virtues? Must George Washington be only the father of our country or an enslaver? Isn’t he both?

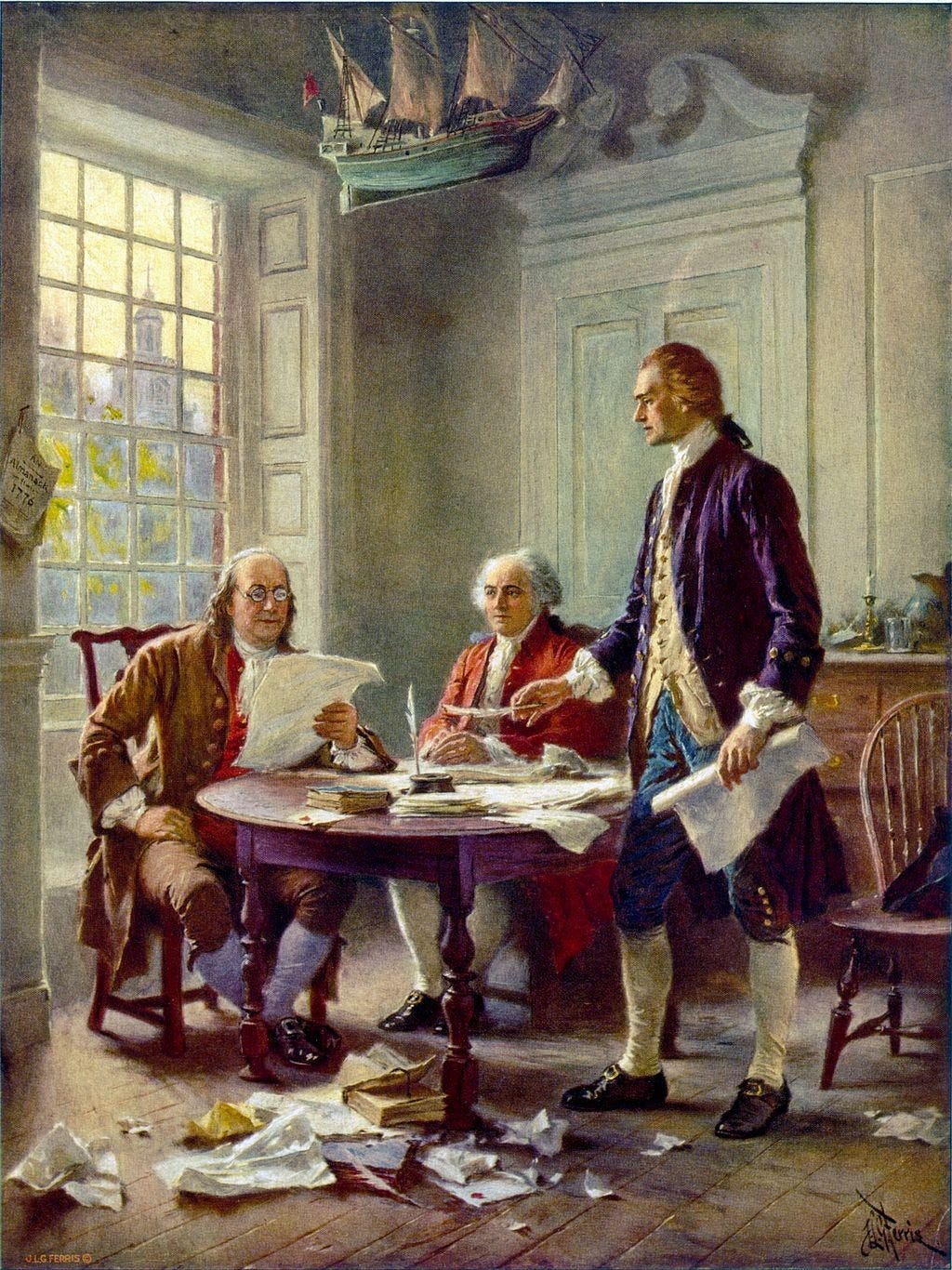

It does not have to be so difficult to say that Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of the Independence AND he enslaved human beings. It is precisely because both of those facts are true2 that I find the history of the United States so compelling. Like a Shakespearean hero, it is a story of a nation forever stumbling as it endeavors to live up to its best self— our national creed that “all men are created equal” and there is “liberty and justice for all,” despite the existence of slavery from the beginning.

I use the word “stumbling” deliberately. As any athlete knows, when you stumble, you get back up. Some might argue that this leads to a simplistic, whiggish view of teaching U.S. history, but I’m not talking about what we do in graduate seminars or even undergraduate intro classes. When we teach our nation’s history in K-12 classrooms, we have to teach the “getting back up” part, or we risk undermining our students’ sense of agency and ability to effectuate positive change.

So how do educators thread this needle? How do we teach about the dark sides of our nation’s history without either crushing the souls of our youth or turning them into zealous flag-waver? It is not easy.

Though I vary it from year to year, on the first day of school (I teach middle school U.S. history) I initiate a discussion about the point of learning history by beginning with the first words of the U.S. Constitution. I do it in 3 “chunks,” emphasizing the ideas below.

The first 3 words — “We the People” — illustrate that the ultimate power in our country resides with the people, not the President, not the Congress, not the Supreme Court.

The second 4 words — “of the United States” — how do we define who the people of the United States are, and how that definition has changed over time? Who is included in the body politic?

The next 8 words— “in order to form a more perfect Union” — emphasis is mine. Why did the authors include the word “more” and what does that suggest?

I can tell you that no middle schooler thinks our country is perfect. They know the answer to the last question above; they know the U.S. isn’t without flaws and that perfection is not likely possible, hence, “more perfect.” While I’ve never taught grade school, my experience as a parent confirms that even much younger children understand can understand basic nuances surrounding good and evil. Every child has done “a bad thing” and yet likely does not think of themself as a “bad person.” We all have been mean to a friend or a sibling; we have all had someone been mean to us, but that doesn’t mean the friendship ends.

Students are not stupid. If we only amplify the virtues, they will mistrust their education. If we only amplify the flaws, I am less fearful they will hate their country and more concerned that they will become indifferent and apathetic towards it. That’s what happens when we become cynical: we stop caring and no longer believe that anything we do can make a difference.

Patriotism is accessible to all of us, no matter our political persuasions.3 If one of the goals of public education— and teaching U.S. history specifically— is to build a better citizenry, then we have to thread this needle and teach patriotism responsibly. Even, or maybe especially, when it feels like walking on a tightrope.

https://rollcall.com/factbase/trump/transcript/donald-trump-speech-mount-rushmore-independence-day-july-3-2020/

Even the most basic facts in history are complicated. Or, to put it positively, there are fascinating backstories to even the most basic facts. Thomas Jefferson was part of a committee of five to author the Declaration. The other four included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston and Roger Sherman. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson eventually became what some might call “frenemies.” Years later, Adams came to resent that Jefferson had gotten so much of the credit for the Declaration, when Adams had played such a fundamental role in moving the colonies toward independence. In an 1822 letter, he concurs with Thomas Pickering that “there is not an idea in [the Declaration] but what had been hackneyed in Congress for two years before.” He goes on to explain why it was that Jefferson was selected as the writer, and why the committee declined to make any substantive changes to it (“We were all in haste. Congress was impatient….”) So was Jefferson the actual writer? Yes. Were the ideas all his? No. Even Jefferson knew that. In a letter to Henry Lee towards the end of his life, Jefferson pointed out that the Declaration was “Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.”

And in case you don’t know the most interesting story about all this, that letter was written one year and almost two months before Jefferson died on the Fourth of July, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration. And the exact same day that Adams died.

Others more eloquent than I have expressed the importance of this work and the reason we need to do it. See, for example, the work of Eric Liu’s Citizen University and Michael Sandel. I’m thinking especially of a discussion Sandel had last November with Walter Isaacson on Amanpour & Co. in which he said, “Democrats and progressives have allowed the Right and the MAGA movement to claim a kind of monopoly on national pride, make America great again. Well, there are a lot of problems with that, but it suggests it speaks to the aspiration for national pride. There is a tendency, understandably, to say, well, that’s what, that’s the MAGA project, a kind of hyper nationalism that is ungenerous to immigrants and to outsiders and to inclusiveness. But the answer to that is not to cast a kind of suspicion on all things patriotic, but to articulate a progressive vision of what patriotism and national pride and a sense of community can mean otherwise.”

Hey Lauren, I am making the jump from elementary to middle school and will be teaching US history. I found your US history blog which led me here. Great post by the way, it is so important to teach the "sinner and saint" in every person, in every idea, and in every history. I have experience with this at an elementary level. In your experience, what is the difference between teaching in this way between elementary and middle and high school? Also, do you know of any resources which talk about teaching US history to middle schoolers vs. high schoolers? Thanks!