Curiosity in the Classroom

So much has changed in education. But kids being curious? Has that changed?

Talk to any teacher who has been at it for more than a dozen years and you are bound to hear some depressing stories about “kids today.” They can’t read, they can’t write, they’re addicted to their phones, they can’t do basic math without a calculator, they won’t do homework, the list goes on. And underneath these complaints are fears about AI and how that will change education and make all those other problems worse. Then you might hear some relief from some of them that they’ll be retiring soon and won’t have to deal with all that.

But there is one thing that, in my opinion, has not changed. Kids are curious. So are teenagers, though it may be harder to detect, lurking as under the armor of their hoodies. Human beings are naturally curious.1

My teaching experience is with middle and high school students, two groups thought to be far less curious than grade-schoolers and often bored. (Just saw Inside 2 over the holiday. Oh, how I loved Ennui!)

If you are a parent of an adolescent, you know the standard reply to what they did in school today: “nothing.” If you’re able to pry anything out of them, it is rarely delivered with enthusiasm.

And while many—dare I even say most— students are often bored in school, it is not because kids aren’t curious or interested in learning. A skeptic might suggest that they aren’t curious about academic things. That isn’t true. As long as those academic things shed light on the world they inhabit, kids will be interested.

When I reflect on particular lessons I’ve taught or parts of lessons that have been the most successful, it’s always been because the topic is interesting. How something has been taught has rarely mattered; it’s what was was learned that matters.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some topics that are interesting that I couldn’t turn into good lessons. That’s on me. But even the teacher of the year can’t make a good lesson if it isn’t about something compelling.

I am a history teacher, so I will use the study of history as my example.

It is absolutely possible to graduate from high school, get into a “good” college and find a well-paying job without knowing much about history. While I deeply believe that knowledge of civics and history is critical on a societal level for maintaining our democracy, it is not essential for individual advancement.

However, education is not just about individual achievement. It is not even wholly about maintaining our democracy or turning out good workers. It is, I think, about living a good life. A rich life.2 Education helps us do that. The word “history” comes from the Latin word “historia” by way of Greek. The ancient Greek word “istor” meant knowledge or a learned person. As Socrates put it, the unexamined life is not worth living.

People want to know about the world they live in. It won’t get anyone a job, but hearing the stories about people and places are enchanting. Stories like the one about John Adams and Thomas Jefferson dying on the exact same day which happened to be the 50th anniversary of Declaration of Independence. Or about how F.D.R. and Churchill met in Casablanca during World War II and the Germans found out, but they thought Casablanca meant the “casa blanca”—the White House. Or about how Booker T. Washington was almost lynched on a train, but the would-be assassins didn’t think to look for him in an expensive Pullman sleeping car.

Unless you are a lump, you probably find the above at least mildly interesting.3 In context, with the appropriate background knowledge (my students had previously done a deep dive into the Pullman Strike of 1894), you would probably find it even more interesting.4

History helps us answer questions, from the mundane to the profound. Why was our nation’s capital was built on a swamp in the middle of nowhere? Why do Democrats have a donkey and Republicans an elephant as party symbols? Why is a vacation to the former tourist playground of Cuba no longer possible for Americans? Why do we have troops all over the world? Did the Philippines really used to be a U.S. colony? Why? Are the 2020s the new 1850s?

One of my favorite lessons to teach is one about Franklin D. Roosevelt’s disability. We cover the basics: what his disability was, how he got polio, what polio is, how and why he hid the fact that he was in a wheelchair from the public, and how was it possible to hide such a thing. The lesson then evolves into a discussion about leadership, power and weakness, disability and strength. We talk about our own senator, Tammy Duckworth (IL) and the governor of Texas, Greg Abbott. Disabilities from birth vs. accidents vs. war injuries vs. the elderly (quite topical with Trump and Biden).

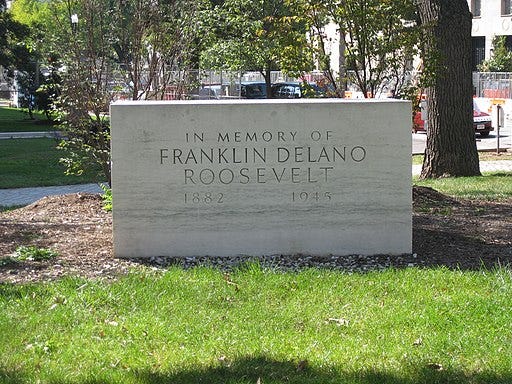

The lesson concludes with a discussion about monuments and memorials in light of F.D.R.’s wish for a simple memorial (the plaque that is outside the National Archives) and the elaborate one built in the 1990s. Quite a bit of controversy ensued over whether or not to depict F.D.R. in his wheelchair. Students reflect, debate and discuss.

Should a memorial to FDR show him in a wheelchair if that was not how he normally appeared to the public?

Why do we build memorials in the first place? Who are they for? The person they are commemorating or us?

Would FDR be upset if the disability he concealed was shown in his memorial?

Does it matter what he would think? What about what his family would want?

Would it be “rewriting history” to show the disability he hid from the world? Or is it “whitewashing” history to leave it out?

To the best of my knowledge, there are few students who don’t find at least some part of this lesson interesting. Except for a few who have seen the memorial live, they are always curious to know what was finally decided, below.

Curiosity is real. It can be present in all our classrooms, no matter what subject, if we let it in. To do that, we need meaningful, content-driven curriculum and teachers who are thoughtful, knowledgeable and have some imagination and curiosity themselves.

Oh, and it wouldn’t hurt to get rid of the phones either.

I know they are curious because I was curious about whether or not that was actually true, and so I looked it up using AI. Found out a lot of cool stuff, including scientific confirmation that human beings are naturally curious. Some view it as an evolutionary advantage. Humans that were curious sought to explore and understand their environment, giving them an advantage on survival. There are different kinds of curiosity, including epistemic, perceptive and diversive. So interesting that I may use my brief foray into the research to write a whole post on it. In the meantime, you might entertain your own curiosity about curiosity by asking ChatGBT to tell you more, or check out this site: The ‘Why’ Behind Asking Why: The Science of Curiosity.

We could argue about what we mean by a good or rich life. That is the job of philosophers, and of course, for all of us to decide for ourselves.

Might I be wrong? If so, challenge me. Comment on this post.

Without context, facts like these are not at all relevant or interesting. Of course I have had students who don’t know who Churchill is or that Casablanca is a city in Morocco. And I doubt any of them have them have heard of Booker T. Washington before they’ve taken my class.